From Developer to Product Engineer: Embracing the Next Abstraction Layer

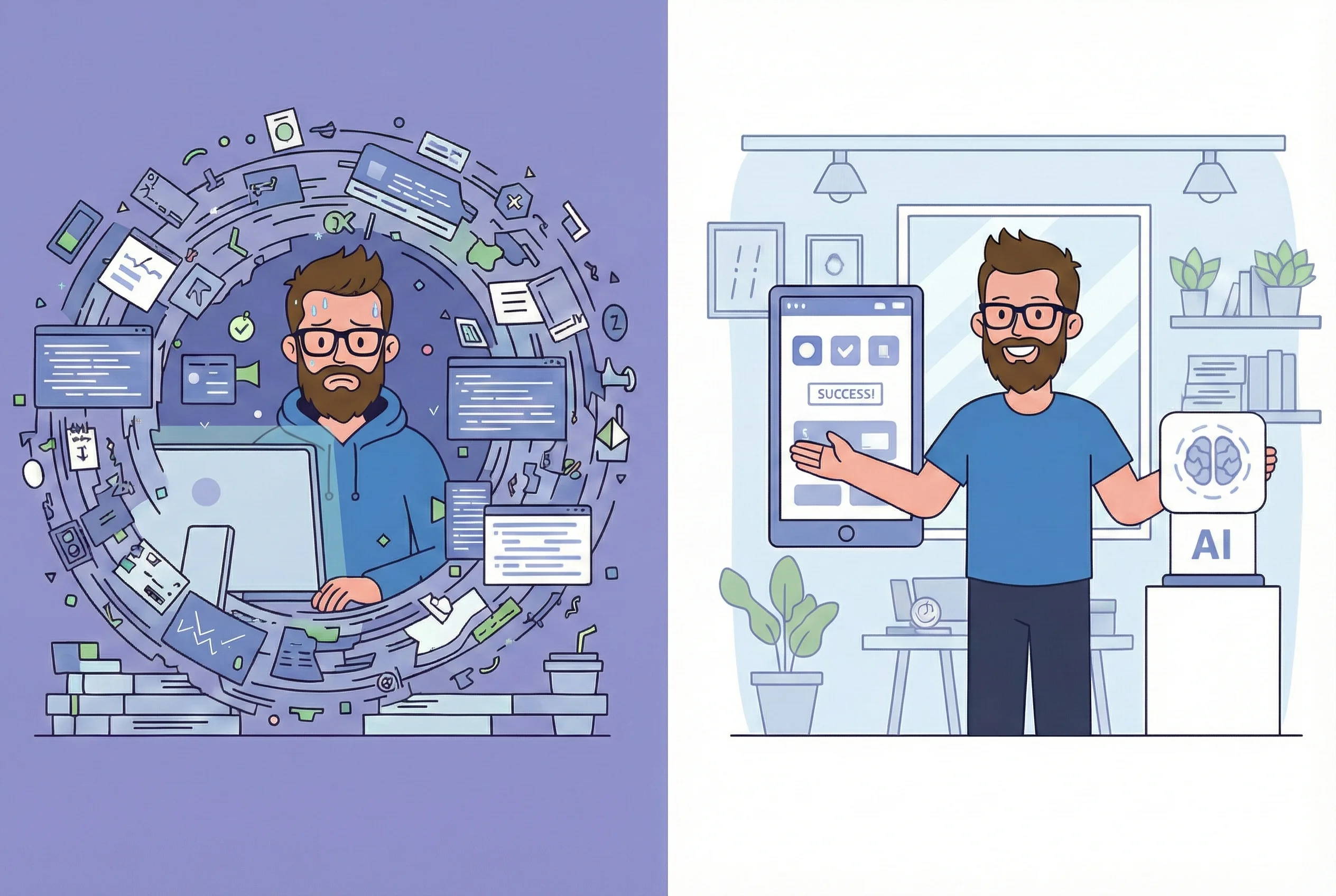

In September 2025, I wrote about my early experiments with AI coding tools and the unexpected power of no-code platforms. Six months later, I’ve come to understand what’s really happening: we’re living through another abstraction leap in the history of software development.

And honestly? It’s brought me more joy in my work than I’ve felt in years.

The Abstraction Ladder

Think about the history of programming. Each generation built a layer on top of the previous one, trading raw control for productivity.

In the 1940s, programmers worked directly with machine code, binary instructions fed to the hardware. The limited speed and memory forced hand-tuned optimizations for every operation. Then in 1949, assembly language emerged with the EDSAC computer, giving human-readable mnemonics to machine instructions. Still low-level, but no longer pure binary.

The 1950s brought the first high-level languages. FORTRAN (1954), created by John Backus at IBM, proved that compiled code could be practical for real work. It’s still used today for supercomputer benchmarks. ALGOL (1958), developed by American and European computer scientists together, established syntax patterns that would influence nearly everything that followed.

Dennis Ritchie created C in 1972 at Bell Labs, abstracting away registers and memory addresses while staying close enough to the metal for systems programming. C became the foundation: C++, Java, JavaScript, Python, all trace their lineage back to it.

The object-oriented era added another layer. Simula pioneered concepts like classes, inheritance, and garbage collection. C++ (1983) brought these to mainstream systems programming. Java (1995), designed by James Gosling at Sun Microsystems, added the JVM layer, compiling to bytecode that could run anywhere. Python pushed further toward human readability, trading performance for accessibility.

AI-assisted coding is simply the next rung on this ladder.

It abstracts away the mechanical act of writing code. Not the thinking, not the architecture, not the product decisions, but the typing, the syntax, the boilerplate, the “how do I do X in this framework again?” moments that consume so much of a developer’s day.

The pattern is consistent: each layer simplifies human interaction while adding computational complexity underneath. We went from manually managing registers to letting compilers handle it, from manual memory allocation to garbage collection, from writing every function to importing libraries. Now we’re moving from typing code to describing intent.

This doesn’t diminish what came before. We still need people building compilers, writing frameworks, optimizing libraries. Just like someone still writes assembly for firmware and kernel code. But for building products, the applications that sit on top of all these layers, the abstraction has moved up once again.

What Actually Changed in My Work

Let me be concrete. In the past year, I’ve shipped:

- Full-scale products with containerized deployments across various cloud providers

- Infrastructure as code, no more clicking around in cloud consoles

- CI/CD pipelines with automated testing and multi-environment deployments

- Backend services in Node.js and Python, choosing the right approach for each project

- Rapid prototypes that validated ideas in hours instead of weeks

The specific tools don’t matter, they’ll change. What matters is the methodology: I describe what I want, I iterate with an AI assistant, I review and refine, I ship. The assistant I use today might be replaced by something better tomorrow. That’s fine. The abstraction layer is what persists.

I wrote dramatically less code than I would have two years ago, yet delivered more complete, more polished products.

The Joy of Delivering Value

Here’s what surprised me most: I’m happier in my work than I’ve been in a long time.

Not because I’m lazy. Not because I’ve somehow “cheated” the system. But because the gap between “I have an idea” and “users can experience it” has shrunk dramatically.

For years, I had notebooks full of product ideas that never got built. Not because they were bad ideas, but because the implementation cost was too high for side projects. Each one required weeks of setup, configuration, boilerplate, debugging, before I could even start on the interesting parts.

Now? I can validate an idea in an afternoon. I can build a working prototype while the enthusiasm is still fresh. I can iterate based on real user feedback instead of theoretical assumptions.

The bottleneck has shifted from “can I build this?” to “should I build this?”, and that’s exactly where it should be.

Where This Doesn’t Apply

Let me be clear about the boundaries. AI-assisted development is phenomenal for building products, applications, tools, services that solve user problems. It’s a force multiplier for turning ideas into reality.

But there are domains where this abstraction layer doesn’t belong.

I wouldn’t want AI-generated code managing a nuclear power plant without exhaustive human review. I wouldn’t trust it for pharmaceutical experiment protocols without rigorous verification, having worked at GSK in a former life, I know how critical those checklists are. Safety-critical systems, regulatory compliance, anything where “mostly correct” isn’t good enough, these still require meticulous human oversight and often pixel-perfect precision.

The abstraction works for product development, internal tools, MVPs, and yes, even production systems where the failure mode is “user sees an error message” rather than “catastrophic real-world consequences.”

Know your context. Choose your tools accordingly.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Development Jobs

Here’s something the industry doesn’t like to discuss openly: most traditional development jobs are going to disappear.

Not all of them. We’ll always need engineers building the foundational blocks, the frameworks, the libraries, the infrastructure that everything else runs on. Someone has to work at the lower abstraction levels, just like someone still writes assembly for firmware and kernel code.

But the vast middle, developers whose job is primarily translating specifications into code, writing CRUD applications, building standard web apps, that work is being automated away. The code itself is becoming commodity. What remains valuable is understanding what to build, why to build it, and how all the pieces fit together.

This isn’t a prediction. It’s already happening. I see it in hiring patterns, in team structures, in what companies pay premiums for. The future belongs to people who can leverage these tools effectively, not to those who can write more lines of code per hour.

LLMs Are Not AGI, And That’s Fine

Let’s be precise about what’s happening. Large language models are not general intelligence. They’re not going to replace human judgment, creativity, or strategic thinking anytime soon.

What they are is remarkably good at one specific thing: leveraging patterns from vast amounts of code and documentation to generate reasonable implementations of well-specified requirements.

That’s not consciousness. It’s not understanding. It’s sophisticated pattern matching and interpolation. But for the task of “turn this description into working code,” sophisticated pattern matching turns out to be exactly what you need.

The abstraction works because most code follows patterns. Most problems have been solved before. Most implementations are variations on themes the model has seen thousands of times. When you need something genuinely novel, a new algorithm, a creative solution to an unprecedented problem, you still need human insight. But most development work isn’t that. Most development work is applying known solutions to new contexts.

And that’s precisely what LLMs excel at.

The Dependency Problem

Here’s an irony: while writing this very article, my AI assistant became unavailable. The infamous 529 error, “Overloaded.” The service I depend on for my daily work simply stopped responding.

This is the uncomfortable reality of building on top of external AI services. You’re adding a dependency that you don’t control. When the API goes down, when the model gets updated and behaves differently, when the pricing changes, when the company pivots, you’re exposed.

It’s not unlike the early days of cloud computing. “What if AWS goes down?” people asked. And sometimes it did. Companies learned to build redundancy, to have fallback plans, to not put all their eggs in one basket.

The same thinking applies here. I use AI assistants daily, but I make sure I can still function without them. I understand what the generated code does. I can debug it, modify it, extend it manually if needed. I keep my fundamental skills sharp even as I delegate the mechanical work.

This matters for another reason: the abstraction layer only works if you understand what’s beneath it. A developer who can’t read the code their AI generates is flying blind. When something breaks, and it will, you need to be able to dig into the lower layers and fix it.

Every abstraction leaks eventually. C programmers still occasionally need to think about assembly. Java developers sometimes need to understand bytecode. AI-assisted developers need to understand the code they’re shipping.

The tools amplify your capabilities, but they can’t replace your understanding.

My Role Has Fundamentally Changed

I used to be a senior developer. My value was in writing code, specifically, in writing better code faster than junior developers, with fewer bugs and cleaner architecture.

Now I’m something different. I spend my time on:

- Product definition: What are we building and why?

- Architecture decisions: How do the pieces fit together at scale?

- User experience: Does this actually solve the user’s problem?

- Integration design: How does this connect to existing systems?

- Quality verification: Is the generated code actually correct?

- Edge case thinking: What happens when things go wrong?

I write less code. I think more about products. I deliver more value.

The job title might say “engineer,” but the actual work is closer to product architect with implementation superpowers. I can prototype my ideas immediately. I can validate architectural decisions with working code. I can iterate on user feedback in real-time.

For the first time, my technical skills and my product instincts are fully aligned. The implementation is no longer the bottleneck.

This Won’t Stop

The abstraction ladder keeps extending upward. What we’re experiencing now is not the end state, it’s a transition point.

Future tools will be better. They’ll require less supervision. They’ll handle more edge cases automatically. They’ll integrate more seamlessly into our workflows. The specific assistant I use today will seem primitive in three years, just like the tools from 2024 seem primitive now.

The response isn’t to resist this change, it’s to surf the wave. Stay current with the tools. Adapt your skills to the new reality. Focus on the parts of the work that remain uniquely human: understanding users, making judgment calls, seeing the big picture.

The developers who thrive will be those who embrace the abstraction and focus on the higher-level work it enables. The developers who struggle will be those who define their identity by lines of code written rather than problems solved.

The Bottom Line

Six months ago, I was experimenting with AI coding tools. Today, I understand them as the next step in a long history of abstraction layers that have made software development progressively more accessible and productive.

I write less code than ever. I ship more products than ever. I spend less time on implementation details and more time on decisions that matter.

And I’m having more fun than I’ve had in years.

Not because the work is easier, it’s not, really. The challenges have just shifted to higher levels of abstraction. But because the gap between imagination and implementation has collapsed. Because I can build things that would have taken months in days. Because the mechanical friction that used to drain my energy is largely gone.

The future of development isn’t about writing code. It’s about building products. The tools will keep changing, the ones I use today will be obsolete soon enough. But the abstraction layer is here to stay.

We’re all becoming product engineers now. The only question is whether you’ll embrace it or fight it.

I know which path brings me joy.

Building products in 2026 feels different. Not easier, exactly, but more direct. The distance between idea and reality has shrunk. For someone who always cared more about the “what” than the “how,” that’s a gift. The abstraction layer keeps rising, and I’m happy to rise with it.